Posts Tagged ‘adversity’

If You’re Not Emotionally Committed, You’re Not Going To Have A High Degree Of Success

Depths of personal commitment allowed the great leaders to execute well in all aspects of their business, as well as to overcome any barriers and adversities they encountered. Sam Walton (Wal-Mart) noted, “I think I overcame every single one of my personal shortcomings by the sheer passion I brought to my work. I don’t know if you’re born with this kind of passion, or if you can learn it. But I do know you need it. If you love your work, you will be out there every day trying to it the best you possibly can, and pretty soon everybody around you will catch the passion from you – like a fever.”

Admiral Hyman Rickover (U.S. Navy) supported this perspective when he stated, “When doing a job – any job – one must feel that he owns it, and act as though he will remain in that job forever. He must look after his work just as conscientiously as though it were his own business and his own money. If he feels he is only a temporary custodian, or that the job is just a stepping-stone to a higher position, his actions will not take into account the long-term interests of the organization.

His lack of commitment to the present job will be perceived by those who work for him, and they, likewise will tend not to care. Too many spend their entire working lives looking for the next job. When one feels he owns his present job and acts that way, he need have no concern about his next job. In accepting responsibility for a job, a person must get directly involved. Every manager has a personal responsibility not only to find problems, but to correct them. This responsibility comes before all other obligations, before personal ambition or comfort.”

John Thompson (Symantec) echoed Rickover’s sentiments when he asserted, “Philosophically, I believe that business is personal, that if you don’t take it personally, you won’t get anything out of it. If you don’t get personally involved in what you get done—if you’re not emotionally committed to it—it’s unlikely that you’re going to have a high degree of success.”

A depth of personal commitment was evident among most of the great leaders surveyed. Mary Kay Ash (Mary Kay) was deeply committed not only to the success of her business, but also to the women who sold her products. Henry Luce, founder of Time Magazine, demonstrated his commitment on multiple levels. “Luce was a missionary’s son and he brought a sense of mission to journalism – it was a calling, and he approached Time Inc. as both capitalist and missionary. His goal was not only to have the most successful media enterprise, but he took very seriously his responsibility to inform and educate his readers, to raise the level of discourse in this country. Whether he succeeded or not is subject to debate, but there is no denying the depth of his commitment.”

A notable example of an observable depth of commitment that had a lasting impact and influence on America is George Washington. It was illustrated within his papers. “Washington’s writings reveal a clear, thoughtful, and remarkably coherent vision of what he hoped an American republic would become… His words, many of them revealed only for family and friends, reveal a man with a passionate commitment to a fully developed idea of a constitutional republic on a continental scale, eager to promote that plan wherever and whenever circumstance or the hand of Providence allowed.”

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It. (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI 2011)

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2014 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

Have You Ever Been Overwhelmed By Your Personal Circumstances?

Have you ever been overwhelmed by your personal circumstances? The current recession has caused many to despair over the problems that seem to overwhelm them… lost jobs, downsizing, pay cuts, you name it. Many just want to give up and quit!

What can the experience of the great leaders teach us? Despite nearly hopeless circumstances, the great and influential leaders’ steadfastness, perseverance and personal drive would never allow them to consider quitting.

Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines) faced overwhelming challenges when he initially launched his airline. He was immediately sued by his competition to prevent Southwest Airlines from making its first flight. He described his experience, “For the next four years the only business Southwest Airlines performed was litigation, as we tried to get our certificate to fly. After the first two years of defending lawsuits, we ran out of money. The Board of Directors wanted to shut down the company because we had no cash. So I said, ‘Well guys, suppose I just handle the legal work for free and pay all of the costs out of my own pocket, would you be willing to continue under those circumstances?’ Since they had nothing to lose, they said yes. We pressed on, finally getting authorization to fly…

Our first flight was to take off on June 18, 1971 and fly between Dallas, Houston and San Antonio. I was excited about being in the airline industry because it’s a very sporty business. But the regulatory and legal hoops enraged me. I thought if we can’t start a low cost airline and the system defeats us, then there is something wrong with the system. It was an idealistic quest as much as anything else. When we brought the first airplane in for evacuation testing (a simulated emergency situation) I was so excited about seeing it that I walked up behind it and put my head in the engine. The American Airlines mechanic grabbed me and said if someone had hit the thrust reverser I would have been toast. At that point I didn’t even care. I went around and kissed the nose of the plane and started crying I was so happy to see it.” [1]

Conrad Hilton (Hilton Hotels) went bankrupt during the Depression. “Faced with challenges that might have seemed insurmountable, he did what he had done since he was a boy—resolved to work hard and have faith in God. Others, it seemed, made up their minds to put their faith in Hilton. He was able to buy goods on credit from locally owned stores because they trusted his ability and determination to one day pay them back. As the kindness of others and his own ingenuity helped him rebuild his hotel empire to proportions previously unheard of, he solidified his commitment to charity and hospitality—two characteristics that became hallmarks both of Hilton Hotels and of the man who began them.” [2]

Walter and Olive Ann Beech (Beech Aircraft) started their company during the Depression. “‘She was the one that kept trying to get the money together to pay the bills,’ said Frank Hedrick, her nephew, who worked with her at Beech for more than 40 years and who succeeded her in 1968 as president of Beech Aircraft…

She said she didn’t give much thought to the problems of starting a new company at a time when most airplane companies were closing, not opening. ‘Mr. Beech thought about that,’ she said. ‘(But) he had this dream and was going to do it. He probably didn’t know how long the Depression was going to last.’ The first few years were difficult, she said. They sold few airplanes. ‘We had to crawl back up that ladder.’” [3]

Olive Ann Beech overcame additional adversity, when she took over the company, after her husband contracted encephalitis during the Second World War and again, after he suddenly died in 1950.

Joyce Hall (Hallmark) saw his company literally go up in smoke, three years after he started it, when his business burned to the ground. “Hall was $17,000 in debt when a flash fire wiped out his printing plant. Luckily, he was able to sweet-talk a local bank into an unsecured $25,000 loan, and he has not taken a step back since. By the late 1930, Hallmark was one of the top three cards.” [4]

Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines) “never considered giving up, despite having a wife and four children at home. Did stress keep him awake nights? No, Kelleher says he was already awake nights, working at his office. ‘I figured if I was working when they were sleeping, it gave me an edge.’ And when he was home, ‘the iron curtain came down,’ walling off the business worries.” [5]

Milton Hershey (Hershey Foods) failed miserably in his first endeavor, a confectionary store in Philadelphia. “In 1886, he was penniless. He went back to Lancaster but did not even have the money to have his possessions shipped after him. When he walked out to his uncle’s farm, he found himself shunned as an irresponsible drifter by most of his relatives.

This time, though, fortune finally smiled on Mr. Hershey. William Henry Lebkicher, who had worked for Hershey in Philadelphia, stored his things and helped him pay the shipping charges. Aunt Mattie and his mother began once again to help him and Milton started experiments which led to the recipe for ‘Hershey’s Crystal’ a ‘melt in your mouth’ caramel candy made with milk.” [6]

“In 1924 [Clarence] Birdseye (Birdseye Foods) helped form the General Sea Foods Co. in Gloucester, Mass., and he began freezing food on a commercial scale… But despite an infusion of cash from a few investors as well as the creation of specially made freezers to hold his product, the country was not yet ready to accept the prospect of frozen food. It took another seven years before Birdseye’s vision came to fruition. As time passed, he continued his experiments with the quick-freezing process… Almost bankrupt, Birdseye continued to press for believers in his inventions. In 1925 he found one in the guise of Postum Cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post.” [7]

Walt Disney (Disney) not only went bankrupt, but also experienced additional adversities. “The company failed due to Disney’s inability to manage the finances, but Disney persevered, continuing to believe in himself and in his dream. He teamed up with his brother, who took care of the financial side of the business and the two moved to Hollywood to found Disney Brothers’ Studio.

But there would still be stumbling blocks. The studio created the popular Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoon character for Universal, but when Disney requested an increase in budget, producer Charles B. Mintz instead hired away most of Disney’s animators and took over production of the cartoon in his own studio. Universal owned the character’s trademark, so there was little Disney could do.

After the Oswald fiasco, Disney set about creating a new cartoon character to replace Oswald. That character became one of the most recognizable symbols in the world: Mickey Mouse.” [8]

[1] Kristina Dell, Airline Maverick (Time Magazine, September 21, 2007)

[2] Gaetz Erin, Conrad Hilton’s Secret of Success (American Heritage People, August 2, 2006)

[3] Earle Joe, Olive Ann Beech Rose to Business Greatness (The Wichita Eagle, February 11, 1985)

[4] The Greeting Card King (Time Magazine, November 30, 1959)

[5] Vinnedge Mary, From the Corner Office – Herb Kelleher (Success Magazine, 2010)

[6] Milton S. Hershey: 1857-1945 (Milton Hershey School; mhs-pa.org)

[7] Elan Elissa Clarence Birdseye (Nation’s Restaurant News, Feb, 1996)

[8] Bostwick Heleigh, Turning a Dream into a Kingdom: The Walt Disney Story (LegalZoom, July 2009)

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI 2011)

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2013 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

The Bonding Power of Shared Sacrifice

There is a strong bond created between leaders and employees, shareholders and constituencies who share sacrifices for the good of the organization.

To make my point, I need to set the stage. I would like to quote from an article by George L. Marshall, Jr., The Rise and Fall of the Newburgh Conspiracy: How General Washington and his Spectacles Saved the Republic

“By early 1783, active hostilities of the American Revolutionary War had been over for nearly two years and commissioners Franklin, Jay, and Adams were still negotiating in Paris to establish a final treaty with Great Britain. With a formal peace almost secured and with no fighting to do, the Continental army had grown bored and restless, but Congress had decided to retain it as long as the British remained in New York to ensure that the gains of seven years of fighting would not be lost.

Disillusionment and doubt had been building among many officers of the army, then headquartered at Newburgh, New York. Born out of this growing loss of morale and confidence was a conspiracy to undertake a coup d’etat and establish a military dictatorship for the young United States, a plot to be styled later as the Newburgh Conspiracy. At the last minute, General George Washington, commander in chief of the army, and his reading spectacles intervened and prevented this drastic step from occurring…

By late morning of March 15, a rectangular building 40 feet wide by 70 feet long with a small dais at one end, known as the Public Building or New Building , was jammed with officers. Gen. Gates, acting as chairman in Washington’s absence, opened the meeting. Suddenly, a small door off the stage swung open and in strode Gen. Washington. He asked to speak to the assembled officers, and the stunned Gates had no recourse but to comply with the request. As Washington surveyed the sea of faces before him, he no longer saw respect or deference as in times past, but suspicion, irritation, and even unconcealed anger. To such a hostile crowd, Washington was about to present the most crucial speech of his career.

Following his address Washington studied the faces of his audience. He could see that they were still confused, uncertain, not quite appreciating or comprehending what he had tried to impart in his speech. With a sigh, he removed from his pocket a letter and announced it was from a member of Congress, and that he now wished to read it to them. He produced the letter, gazed upon it, manipulated it without speaking. What was wrong, some of the men wondered. Why did he delay? Washington now reached into a pocket and brought out a pair of new reading glasses. Only those nearest to him knew he lately required them, and he had never worn them in public. Then he spoke:

“Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.”

This simple act and statement by their venerated commander, coupled with remembrances of battles and privations shared together with him, and their sense of shame at their present approach to the threshold of treason, was more effective than the most eloquent oratory. As he read the letter to their unlistening ears, many were in tears from the recollections and emotions which flooded their memories. As Maj. Samuel Shaw, who was present, put it in his journal, ” There was something so natural, so unaffected in this appeal as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory. It forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye.”

Finishing, Washington carefully and deliberately folded the letter, took off his glasses, and exited briskly from the hall. Immediately, Knox and others faithful to Washington offered resolutions affirming their appreciation for their commander in chief, and pledging their patriotism and loyalty to the Congress, deploring and regretting those threats and actions which had been uttered and suggested. What support Gates and his group may have enjoyed at the outset of the meeting now completely disintegrated, and the Newburgh conspiracy collapsed.”

George Washington is the premier role model in the history of American leadership for many reasons. There are many legend and myths associated with him. The example of his leadership during the Newbury Conspiracy demonstrates how the bond of shared sacrifice and personal humility literally changed the course of American History. It’s unclear whether Washington intentionally tapped into this power or whether it was unintentional. Regardless he was able to tap into a strong emotional bond forged through sacred sacrifice and adversity.

One might say that was then and this is now. How does Washington apply to me? Leadership goes beyond the bottom line. Leaders recognize the value of the people, especially the right people that they are tasked to lead. Whether fighting a war, building a business or overcoming economic adversity, emotional bonds are formed. Leaders are tested and often experience one or more defining moments. Emerging on the other side of adversity, leaders and their organizations are stronger for it. When future obstacles occur, both are better prepared to handle them. This was one of Washington’s defining moment and his officers were prepared to follow him.

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2013 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

How You Respond to Failure Defines You as a Leader

Every one of us experiences failures and faces adversities. Our response defines us as a leader. The great and influential leaders were no strangers to failure. My research illustrates that most experienced levels of failure and adversity that would compel typical individuals to pack their bags and quit in frustration and disappointment.

The levels of success they achieved did not come easily, but they were persistent. Their personal levels of perseverance and self-reliance are what realistically defined them. Most viewed failure as a learning experience, rather than a defining event. Fred Smith (FedEx) observed, “Just because an idea isn’t implemented or doesn’t work out doesn’t mean that a person has failed.” [1]

Early in his career at Johnson & Johnson, General Robert Wood Johnson taught James Burke a valuable lesson about failure. “Shortly after he arrived at J&J in 1953 as a product director after three years at Procter & Gamble, Burke attempted to market several over-the-counter medicines for children. They all failed-and he was called in for a meeting with the chairman.

‘I assumed I was going to be fired,’ Burke recalls. ‘But instead, Johnson told me, ‘Business is all about making decisions, and you don’t make decisions without making mistakes. Don’t make that mistake again, but please be sure you make others.’”[2]

In 2001, John Chambers (Cisco) saw his company’s revenues and stock price fall off the cliff during the tech and telecom busts. He was challenged with the reality of massive and likely fatal failure. “Within days of realizing Cisco was crashing, Chambers leapt into trying to fix it. ‘He never dwelled on it,’ says Sam Palmisano, CEO of IBM (IBM) … ‘John kept the company focused. He said this is where we are, and he drove the company forward.’

He reached out to [Jack] Welch (General Electric) and a handful of other CEOs. They told him that sudden downturns always take companies by surprise, ‘so I should quit beating myself up for being surprised,’ Chambers recalls. He did. Chambers decided that the free fall had been beyond his control. He now wraps it up in an analogy he retells time and again, likening the crash to a disastrous flood: It rarely happens, but when it does, there’s nothing you can do to stop it… Those other CEOs also told Chambers to figure out how bad it was going to get, take all the harsh action necessary to get through it and plan for the eventual upturn.” [3]

David Packard (Hewlett-Packard) faced failure and adversity in a gruff and straightforward manner. “When he returned to HP in the early 1970s after his stint as deputy secretary of defense and found the company on the verge of borrowing $100 million to cover a cash-flow shortage, he immediately met with employees and gave them what came to be known as a ‘Dave Gives ‘Em Hell’ speech. Packard lined up the division managers in front of employees and told them, ‘If they don’t get inventories under control, they’re not going to be your managers for very long.’ Within six months, the company once again had positive cash flow, to the tune of $40 million.” [4]

John D. Rockefeller (Standard Oil) advised, “‘Look ahead… Be sure that you are not deceiving yourself at any time about actual conditions.’ He notes that when a business begins to fail, most men hate ‘to study the books and face the truth.” [5]

- [1] Federal Express’s Fred Smith (Inc. Magazine, October 1, 1986)

[2] Alumni Achievement Awards: James E. Burke (Harvard Business School, 2003)

[3] Maney Kevin, Chambers, Cisco Born Again (USA Today, January 21, 2004)

[4] O’Hanlon Charlene, David Packard: High-Tech Visionary (CRN, November 8, 2000)

[5] Baida Peter, Rockefeller Remembers (American Heritage Magazine, September/October 1988, Volume 39, Issue 6)

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great, What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI, 2011) Read a FREE Chapter.

Related:

If You Put Fences Around People, You Get Sheep

Does Compassion and Empathy Have a Role in Leadership?

Emotional Bonds are a Reflection of a Leader’s Effectiveness

Do You Have Faith in Your People?

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2013 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

Your Personal Vision Anchors You to Weather Your Storm

Kemmons Wilson – Founder of Holiday Inn

Without personal determination and resolve, persistence and perseverance quickly dissolve under intense and sustained pressures, especially those that are created by adversity and failure. By anchoring themselves in the strength of their personal vision, however, the great leaders were able to withstand both internal and external pressures, strife and feelings of defeat.

This in turn, produced the fortitude and resolve to continue in their pursuits. George Washington’s personal vision of the creation of a republic is what gave him the strength to endure eight harrowing years of leading the American Revolution, and then more to lead the republic in its infancy as its first President.

Kemmons Wilson (Holiday Inn) is another notable example of determination. As an entrepreneur from early on in his youth, he experienced a series of adversities and setbacks. “From the days when he first peddled The Saturday Evening Post as a youngster, through his founding of Holiday Inn, up to his creation of Wilson World and Orange Lake, he has stuck to his goals.” [1]

Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines) faced overwhelming challenges when he initially launched his airline. He was immediately sued by his competition to prevent Southwest Airlines from making its first flight. He described his experience, “For the next four years the only business Southwest Airlines performed was litigation, as we tried to get our certificate to fly. After the first two years of defending lawsuits, we ran out of money.

The Board of Directors wanted to shut down the company because we had no cash. So I said, ‘Well guys, suppose I just handle the legal work for free and pay all of the costs out of my own pocket, would you be willing to continue under those circumstances?’ Since they had nothing to lose, they said yes. We pressed on, finally getting authorization to fly…

Our first flight was to take off on June 18, 1971 and fly between Dallas, Houston and San Antonio. I was excited about being in the airline industry because it’s a very sporty business. But the regulatory and legal hoops enraged me. I thought if we can’t start a low cost airline and the system defeats us, then there is something wrong with the system. It was an idealistic quest as much as anything else.

When we brought the first airplane in for evacuation testing (a simulated emergency situation) I was so excited about seeing it that I walked up behind it and put my head in the engine. The American Airlines mechanic grabbed me and said if someone had hit the thrust reverser I would have been toast. At that point I didn’t even care. I went around and kissed the nose of the plane and started crying I was so happy to see it.” [2]

Conrad Hilton (Hilton Hotels) went bankrupt during the Depression. “Faced with challenges that might have seemed insurmountable, he did what he had done since he was a boy—resolved to work hard and have faith in God. Others, it seemed, made up their minds to put their faith in Hilton.

He was able to buy goods on credit from locally owned stores because they trusted his ability and determination to one day pay them back. As the kindness of others and his own ingenuity helped him rebuild his hotel empire to proportions previously unheard of, he solidified his commitment to charity and hospitality—two characteristics that became hallmarks both of Hilton Hotels and of the man who began them.” [3]

Walter and Olive Ann Beech (Beech Aircraft) started their company during the Depression. “ ‘She was the one that kept trying to get the money together to pay the bills,’ said Frank Hedrick, her nephew, who worked with her at Beech for more than 40 years and who succeeded her in 1968 as president of Beech Aircraft…

She said she didn’t give much thought to the problems of starting a new company at a time when most airplane companies were closing, not opening. ‘Mr. Beech thought about that,’ she said. ‘(But) he had this dream and was going to do it. He probably didn’t know how long the Depression was going to last.’

The first few years were difficult, she said. They sold few airplanes. ‘We had to crawl back up that ladder.’ ” [4] Olive Ann Beech overcame additional adversity when she took over the company after her husband contracted encephalitis during the Second World War, and again, after he suddenly died in 1950.

Joyce Hall (Hallmark) saw his company literally go up in smoke three years after he started it, when his business burned to the ground. “Hall was $17,000 in debt when a flash fire wiped out his printing plant. Luckily, he was able to sweet-talk a local bank into an unsecured $25,000 loan, and he has not taken a step back since. By the late 1930s, Hallmark was one of the top three cards.” [5]

Related:

Does Luck Play a Role in a Leader’s Success?

Are You Willing to Pay the Price to Succeed?

Leaders Possess a Deeply Embedded Sense of Purpose

References:

- Success Secrets of Memphis’ Most Prolific Entrepreneur (Business Perspectives, July 1, 1997)

- Kristina Dell, Airline Maverick (Time Magazine, September 21, 2007)

- Gaetz Erin, Conrad Hilton’s Secret of Success (American Heritage People, August 2, 2006)

- Earle Joe, Olive Ann Beech Rose to Business Greatness (The Wichita Eagle, February 11, 1985)

- The Greeting Card King (Time Magazine, November 30, 1959)

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI 2011) Read a Free Chapter

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2013 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

Are You Willing to Pay the Price to Succeed?

All of the great leaders I surveyed experienced what I describe as the Crucible Principle. It states that:

Individuals experience a prolonged, but undetermined period of adversity, disappointment, discouragement and failure early in their careers, which either refines them or breaks their spirits. How they respond to these circumstances will define their character, refine their critical thinking and establish their legitimacy as a leader.

Individuals who do not undergo crucible development early in their careers will not develop the critical thinking skills and character to handle adversities, problems and crisises that will arise in the future. This will result in more difficulties, which will place them at a disadvantage, and undermine their legitimacy as a leader.

Leadership greatness is achieved only after individuals experience an emotional caldron full of adversity, setbacks, failures and obstacles that refine both their character and their vision.

It is a period where courage and fortitude are tested and cultivated. In general, many individuals who experience the Crucible Principle encounter unrelenting waves of pain, disappointment, chaos, confusion and discouragement. They see no end in sight. They simply give up and quit.

“Resilience from the trials of life’s adversity has always been the filter that separates folk heroes from other leaders. Anthropologist Joseph Campbell profiled ancient leaders across cultures and revealed a shared ability to transcend crushing defeat.

This was rooted in a drive for a lasting legacy that can provide for a mythic sense of purpose to ‘triumph the despair and shame of failure. Setbacks actually challenge us to come back with an even greater sense of mission…

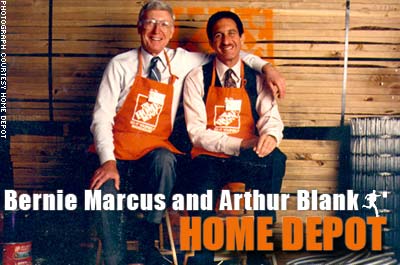

Many other great leaders, such as Home Depot founder Bernie Marcus, Vanguard founder Jack Bogle, Staples founder Tom Steiuherg and Jet Blue founder David Neelenian, created revolutionary enterprises only after having been fired as victims of power struggles.

Others, such as Autodesk’s Carol Bartz, led strategic transformations while battling life-threatening health crises; and some, such as lifestyle maven Martha Stewart, came back as a hugely successful leader following time served in prison. ” [1]

The existence of this principle and the number of times it surfaced was particularly surprising during the course of my research. The great leaders surveyed experienced difficult levels of adversity, including a sizable number of obstacles they had to overcome.

Success didn’t come easy to them, and it was far from automatic. They were relentless in the levels of persistence they demonstrated, buttressed by the strength of their personal vision. They refused to quit and accept failure. When they encountered failure, they picked themselves up and started over again, and sometimes more than once, until they ultimately succeeded.

The existence of the Crucible Principle was supported by the fact that the average age of the leaders surveyed who started their business or achieved their first major corporate position, was 34 years old.

This means between 13 to 16 years of their lives were spent working their way into a position of responsibility. This data is predicted on the assumption that most started working when they were between 18 to 21 years old.

Some notable examples include: Jack Welch, who started his career at General Electric as a junior engineer, almost left in frustration during his first year, Arthur Vining Davis (Alcoa) was the third employee to be hired at the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (Alcoa) as an assistant; and Arthur Blank (Home Depot), who began his career with the Handy Dan Hardware Company, where he worked for 14 years until he was fired as a regional manager.

An additional significant factor was the duration of the application of the Crucible Principle. My research establishes that it averages 12 years in length. This typically is a period filled with pain, heartache, frustration and failure.

The great leaders’ ability to succeed and prevail ultimately determined their future success. For any individual seeking immediate success, this should be an eye opening fact.

During my own younger years a personal mentor constantly reminded me: “The wheel of success turns very slowly.” Some notable examples of the Crucible Principle include Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines), who waged a four-year legal battle before he flew a single passenger, just to incorporate and start-up his airline. During the early years of its existence, he was forced to sell one of his four airplanes to meet his payroll.

It took Joe Wilson, president of the Haloid Company, twelve years of frustration and continuous investment to commercialize a patent that he had purchased for xerography, to produce the first Xerox machine.

Jeff Bezos observed, “Optimism is essential when trying to do anything difficult because difficult things often take a long time. That optimism can carry you through the various stages as the long term unfolds. And it’s the long term that matters.” [2]

Once the great leaders emerged and achieved levels of prominence, they averaged 25 years in their positions. This does not mean that their lives were easy and carefree. These typically were periods of continuing conflict and adversity, yet they also were the most productive periods of their lives.

Malcolm McLean had founded a successful trucking business. Looking for a way to solve shipping bottlenecks and lower overall costs, he used his resources to develop containerizing cargo.

His innovations ultimately revolutionized the shipping industry through the standardization of an integrated system of containers, ships, railroads and harbor facilities. His ideas virtually impact the entire world due to the expansion of global trading.

Henry Flagler made his fortune as John D. Rockefeller’s partner at Standard Oil. He used his considerable financial resources to create the tourism industry in the State of Florida by building railroads and elegant resorts.

Related:

Does Luck Play a Role in a Leader’s Success?

Do You Have the Fortitude and Resolve to Continue?

Leaders Possess a Deeply Embedded Sense of Purpose

Leaders Possess an Absolute Love for What They Do

References:

- Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, Fired With Enthusiasm (Directorship) April 1. 2007

- Rob Walker, Jeff Bezos: Amazon.com – America’s 25 Most Fascinating Entrepreneurs (Inc. Magazine) April 1, 2004

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI 2011) Read a Free Chapter

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2012 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

“Success is the Sum of Details”

Harvey Firestone (Firestone Tire) stated, “success is the sum of details.” The great leaders uniformly paid extraordinary close attention to details.

It is an important attribute or aspect of their thinking. It influenced virtually every aspect of their lives, which ranged from ruthless efficiency to product quality, to how they treated their employees. As architects of growth, their attention to detail allowed them to formulate comprehensive plans and blueprints, which supported the building and growth of their companies.

Many leaders like James J. Hill (Great Northern Railway), Sam Walton (Wal-Mart) and Robert Wood (Sears) all devoured as much data and information as they could get their hands on, to generate detailed plans and blueprints for their business, as did William Boeing (Boeing) and John Jacob Astor. Bill Gates (Microsoft) “also has incredible focus and knowledge of his industry. As Ross Perot once noted, ‘Gates is a guy who knows his product.’ ”

In addition to paying close attention to details, the great leaders developed unparalleled competence and expertise through years of experience. They all emerged from long and dark valleys of frustration, disappointment, adversity and often failure, which tested their mettle, polished their skills and competencies and generated deep levels of perseverance and resilience.

None of the great leaders surveyed ever appeared to succeed without first enduring what I call a long and frustrating “crucible period.” These experiences and the lessons gained within this “crucible period” allowed them to possess the necessary skills, experience and expertise to take advantage of opportunities presented to them. They were able to recognize them for what they were, and knew how to plan and profit from them.

A notable example is Theodore Vail (AT&T). He “left the post office service to establish the telephone business. He had been in authority over thirty-five hundred postal employees, and was the developer of a system that covered every inhabited portion of the country.

Consequently, he had a quality of experience that was immensely valuable in straightening out the tangled affairs of the telephone. Line by line, he mapped out a method, a policy, a system. He introduced a larger view of the telephone business… He persuaded half a dozen of his post office friends to buy stock, so that in less than two months the first ‘Bell Telephone Company’ was organized, with $450,000 capital and a service of twelve thousand telephones.” [1]

In 1902, one hundred years after it was founded, E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, commonly known as DuPont, was sold by the surviving partners to three of the great-grandsons of the original founder, led by Pierre du Pont. He had grown up in the family business and had developed the necessary expertise to assume control over it. He understood the associated problems, issues and weaknesses that needed to be rectified, and drafted and executed the necessary plans to transform the company.

“As chief of financial operations, Pierre du Pont oversaw the restructuring of the company along modern corporate lines. He created a centralized hierarchical management structure, developed sophisticated accounting and market forecasting techniques, and pushed for diversification and increasing emphasis on research and development.

He also introduced the principle of return on investment, a key modern management technique. From 1902 to 1914, Pierre kept a firm rein on the company’s growth, but with the onset of World War I he guided DuPont through a period of breakneck expansion financed by advance payments on Allied munitions contracts.” [2]

As a primary supplier of paints and lacquers required for automotive production, DuPont became a major investor in General Motors. Pierre DuPont replaced William Durant, the company’s founder, as CEO. DuPont made a key decision in promoting Alfred Sloan to the office of president. Sloan developed a detailed blueprint that transformed GM into the largest industrial company the world had ever known at that time.

He “created structure so people could be more creative with their time and have it be well spent. He also came up with the idea that senior executives should exercise some central control but should not interfere too much with the decision making in each operation.

It is difficult to describe many of Sloan’s ideas because most of them would seem like common concepts of a business, yet they were new and innovative at the time. Largely due to his invention, GM became the pioneer in market research, public relations and advertising. Before Sloan, people had totally different conceptions of these common parts of the American corporation.” [3]

Due to Sloan’s success, his corporate model highly influenced the development of the modern American corporation. His theories were actively practiced for over 50 years and remained unchallenged until Jack Welch’s (General Electric) influence permeated the mid-1980s.

Related:

- Do You Have the Talent to Execute Get Things Done?

- Linking Structure to Action

- The Value of Personal Experience and Expertise

References:

- Casson Herbert N., The History of the Telephone. Chapter II (February 1, 1997)

- Pierre S. du Pont: 1915 (www2.dupont.com)

- Alfred P. Sloan, Inventor of the Modern Corporation (Invent Help Invention Newsletter, August 2004)

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI 2011) Read a Free Chapter

T imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

imothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreword Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web| Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2012 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

If You’re Not Emotionally Committed, You’re Not Going To Have A High Degree Of Success

Depths of personal commitment allowed the great leaders to execute well in all aspects of their business, as well as to overcome any barriers and adversities they encountered. Sam Walton (Wal-Mart) noted, “I think I overcame every single one of my personal shortcomings by the sheer passion I brought to my work. I don’t know if you’re born with this kind of passion, or if you can learn it. But I do know you need it. If you love your work, you will be out there every day trying to it the best you possibly can, and pretty soon everybody around you will catch the passion from you – like a fever.”

Admiral Hyman Rickover (U.S. Navy) supported this perspective when he stated, “When doing a job – any job – one must feel that he owns it, and act as though he will remain in that job forever. He must look after his work just as conscientiously as though it were his own business and his own money. If he feels he is only a temporary custodian, or that the job is just a stepping-stone to a higher position, his actions will not take into account the long-term interests of the organization.

His lack of commitment to the present job will be perceived by those who work for him, and they, likewise will tend not to care. Too many spend their entire working lives looking for the next job. When one feels he owns his present job and acts that way, he need have no concern about his next job. In accepting responsibility for a job, a person must get directly involved. Every manager has a personal responsibility not only to find problems, but to correct them. This responsibility comes before all other obligations, before personal ambition or comfort.”

John Thompson (Symantec) echoed Rickover’s sentiments when he asserted, “Philosophically, I believe that business is personal, that if you don’t take it personally, you won’t get anything out of it. If you don’t get personally involved in what you get done—if you’re not emotionally committed to it—it’s unlikely that you’re going to have a high degree of success.”

A depth of personal commitment was evident among most of the great leaders surveyed. Mary Kay Ash (Mary Kay) was deeply committed not only to the success of her business, but also to the women who sold her products. Henry Luce, founder of Time Magazine, demonstrated his commitment on multiple levels. “Luce was a missionary’s son and he brought a sense of mission to journalism – it was a calling, and he approached Time Inc. as both capitalist and missionary. His goal was not only to have the most successful media enterprise, but he took very seriously his responsibility to inform and educate his readers, to raise the level of discourse in this country. Whether he succeeded or not is subject to debate, but there is no denying the depth of his commitment.”

A notable example of an observable depth of commitment that had a lasting impact and influence on America is George Washington. It was illustrated within his papers. “Washington’s writings reveal a clear, thoughtful, and remarkably coherent vision of what he hoped an American republic would become… His words, many of them revealed only for family and friends, reveal a man with a passionate commitment to a fully developed idea of a constitutional republic on a continental scale, eager to promote that plan wherever and whenever circumstance or the hand of Providence allowed.”

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It. (Majorium Business Press, Stevens Point, WI, 2012)

If you would like to learn more about the personal commitment and passion of the great American leaders through their own inspiring words and stories, refer to Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It. It illustrates how great leaders built great companies, and how you can apply the strategies, concepts and techniques that they pioneered to improve your own leadership skills. Click here to learn more.

________________________________________________________________________

Timothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. | Author | Publisher | Majorium Business Press

Author of Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Finalist – 2011 Foreward Reviews‘ Book of the Year)

Linkedin | Facebook | Twitter | Web | Blog | Catalog |800.654.4935 | 715.342.1018

Copyright © 2012 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

Success is the Sum of Details

Harvey Firestone (Firestone Tire) stated, “success is the sum of details.” The great leaders uniformly paid extraordinary close attention to details. Throughout this book it is frequently referenced, since it is an important attribute or aspect of their thinking. It influenced virtually every aspect of their lives, which ranged from ruthless efficiency to product quality, to how they treated their employees. As architects of growth, their attention to detail allowed them to formulate comprehensive plans and blueprints, which supported the building and growth of their companies.

Many leaders like James J. Hill (Great Northern Railway), Sam Walton (Wal-Mart) and Robert Wood (Sears) all devoured as much data and information as they could get their hands on, to generate detailed plans and blueprints for their business, as did William Boeing (Boeing) and John Jacob Astor. Bill Gates (Microsoft) “also has incredible focus and knowledge of his industry. As Ross Perot once noted, ‘Gates is a guy who knows his product.’ ”

In addition to paying close attention to details, the great leaders developed unparalleled competence and expertise through years of experience. They all emerged from long and dark valleys of frustration, disappointment, adversity and often failure, which tested their mettle, polished their skills and competencies and generated deep levels of perseverance and resilience. None of the great leaders surveyed ever appeared to succeed without first enduring what I call a long and frustrating “crucible period.” These experiences and the lessons gained within this “crucible period” allowed them to possess the necessary skills, experience and expertise to take advantage of opportunities presented to them. They were able to recognize them for what they were, and knew how to plan and profit from them. A notable example is Theodore Vail (AT&T). He “left the post office service to establish the telephone business. He had been in authority over thirty-five hundred postal employees, and was the developer of a system that covered every inhabited portion of the country. Consequently, he had a quality of experience that was immensely valuable in straightening out the tangled affairs of the telephone. Line by line, he mapped out a method, a policy, a system. He introduced a larger view of the telephone business… He persuaded half a dozen of his post office friends to buy stock, so that in less than two months the first ‘Bell Telephone Company’ was organized, with $450,000 capital and a service of twelve thousand telephones.”

In 1902, one hundred years after it was founded, E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, commonly known as DuPont, was sold by the surviving partners to three of the great-grandsons of the original founder, led by Pierre du Pont. He had grown up in the family business and had developed the necessary expertise to assume control over it. He understood the associated problems, issues and weaknesses that needed to be rectified, and drafted and executed the necessary plans to transform the company. “As chief of financial operations, Pierre du Pont oversaw the restructuring of the company along modern corporate lines. He created a centralized hierarchical management structure, developed sophisticated accounting and market forecasting techniques, and pushed for diversification and increasing emphasis on research and development. He also introduced the principle of return on investment, a key modern management technique. From 1902 to 1914, Pierre kept a firm rein on the company’s growth, but with the onset of World War I he guided DuPont through a period of breakneck expansion financed by advance payments on Allied munitions contracts.”

As a primary supplier of paints and lacquers required for automotive production, DuPont became a major investor in General Motors. Pierre DuPont replaced William Durant, the company’s founder, as CEO. DuPont made a key decision in promoting Alfred Sloan to the office of president. Sloan developed a detailed blueprint that transformed GM into the largest industrial company the world had ever known at that time. He “created structure so people could be more creative with their time and have it be well spent. He also came up with the idea that senior executives should exercise some central control but should not interfere too much with the decision making in each operation. It is difficult to describe many of Sloan’s ideas because most of them would seem like common concepts of a business, yet they were new and innovative at the time. Largely due to his invention, GM became the pioneer in market research, public relations and advertising. Before Sloan, people had totally different conceptions of these common parts of the American corporation.” Due to Sloan’s success, his corporate model highly influenced the development of the modern American corporation. His theories were actively practiced for over 50 years and remained unchallenged until Jack Welch’s (General Electric) influence permeated the mid-1980s.

[1] Maury Klein, The Change Makers (Henry Holt and Company, LLC, New York, NY 2003) p. 106-107

[2] Casson Herbert N., The History of the Telephone. Chapter II (February 1, 1997)

[3] Pierre S. du Pont: 1915 (www2.dupont.com)

[4] Alfred P. Sloan, Inventor of the Modern Corporation (Invent Help Invention Newsletter, August 2004)

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, 2011)

If you would like to learn more about how the great American leaders attention to details to build plans and blueprints and formulate strategies for their business, refer to Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It. It illustrates how great leaders built great companies, and how you can apply the strategies, concepts and techniques that they pioneered to improve your own leadership skills.Click here to learn more.

Copyright © 2011 Timothy F. Bednarz, All Rights Reserved

Do You Have the Fortitude and Resolve to Continue?

Without personal determination and resolve, persistence and perseverance quickly dissolve under intense and sustained pressures, especially those that are created by adversity and failure. By anchoring themselves in the strength of their personal vision, however, the great leaders were able to withstand both internal and external pressures, strife and feelings of defeat. This in turn, produced the fortitude and resolve to continue in their pursuits. George Washington’s personal vision of the creation of a republic is what gave him the strength to endure eight harrowing years of leading the American Revolution, and then more to lead the republic in its infancy as its first President.

Kemmons Wilson (Holiday Inn) is another notable example of determination. As an entrepreneur from early on in his youth, he experienced a series of adversities and setbacks. “From the days when he first peddled The Saturday Evening Post as a youngster, through his founding of Holiday Inn, up to his creation of Wilson World and Orange Lake, he has stuck to his goals.” [1]

Herb Kelleher (Southwest Airlines) faced overwhelming challenges when he initially launched his airline. He was immediately sued by his competition to prevent Southwest Airlines from making its first flight. He described his experience, “For the next four years the only business Southwest Airlines performed was litigation, as we tried to get our certificate to fly. After the first two years of defending lawsuits, we ran out of money. The Board of Directors wanted to shut down the company because we had no cash. So I said, ‘Well guys, suppose I just handle the legal work for free and pay all of the costs out of my own pocket, would you be willing to continue under those circumstances?’ Since they had nothing to lose, they said yes. We pressed on, finally getting authorization to fly…

Our first flight was to take off on June 18, 1971 and fly between Dallas, Houston and San Antonio. I was excited about being in the airline industry because it’s a very sporty business. But the regulatory and legal hoops enraged me. I thought if we can’t start a low cost airline and the system defeats us, then there is something wrong with the system. It was an idealistic quest as much as anything else. When we brought the first airplane in for evacuation testing (a simulated emergency situation) I was so excited about seeing it that I walked up behind it and put my head in the engine. The American Airlines mechanic grabbed me and said if someone had hit the thrust reverser I would have been toast. At that point I didn’t even care. I went around and kissed the nose of the plane and started crying I was so happy to see it.” [2]

Conrad Hilton (Hilton Hotels) went bankrupt during the Depression. “Faced with challenges that might have seemed insurmountable, he did what he had done since he was a boy—resolved to work hard and have faith in God. Others, it seemed, made up their minds to put their faith in Hilton. He was able to buy goods on credit from locally owned stores because they trusted his ability and determination to one day pay them back. As the kindness of others and his own ingenuity helped him rebuild his hotel empire to proportions previously unheard of, he solidified his commitment to charity and hospitality—two characteristics that became hallmarks both of Hilton Hotels and of the man who began them.” [3]

Walter and Olive Ann Beech (Beech Aircraft) started their company during the Depression. “ ‘She was the one that kept trying to get the money together to pay the bills,’ said Frank Hedrick, her nephew, who worked with her at Beech for more than 40 years and who succeeded her in 1968 as president of Beech Aircraft…

She said she didn’t give much thought to the problems of starting a new company at a time when most airplane companies were closing, not opening. ‘Mr. Beech thought about that,’ she said. ‘(But) he had this dream and was going to do it. He probably didn’t know how long the Depression was going to last.’ The first few years were difficult, she said. They sold few airplanes. ‘We had to crawl back up that ladder.’ ” [4] Olive Ann Beech overcame additional adversity when she took over the company after her husband contracted encephalitis during the Second World War, and again, after he suddenly died in 1950.

Joyce Hall (Hallmark) saw his company literally go up in smoke three years after he started it, when his business burned to the ground. “Hall was $17,000 in debt when a flash fire wiped out his printing plant. Luckily, he was able to sweet-talk a local bank into an unsecured $25,000 loan, and he has not taken a step back since. By the late 1930s, Hallmark was one of the top three cards.” [5]

[1] Success Secrets of Memphis’ Most Prolific Entrepreneur (Business Perspectives, July 1, 1997)

[2] Kristina Dell, Airline Maverick (Time Magazine, September 21, 2007)

[3] Gaetz Erin, Conrad Hilton’s Secret of Success (American Heritage People, August 2, 2006)

[4] Earle Joe, Olive Ann Beech Rose to Business Greatness (The Wichita Eagle, February 11, 1985)

[5] The Greeting Card King (Time Magazine, November 30, 1959)

Excerpt: Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It (Majorium Business Press, 2011)

If you would like to learn more about the fortitude, perseverance and resolve to continue of the great American leaders through their own inspiring words and stories, refer to Great! What Makes Leaders Great: What They Did, How They Did It and What You Can Learn From It. It illustrates how great leaders built great companies, and how you can apply the strategies, concepts and techniques that they pioneered to improve your own leadership skills.Click here to learn more.

Copyright © 2011 Timothy F. Bednarz, Ph.D. All rights reserved.